Why his story returned to public attention now

It is the lingering echo of a familiar voice onstage.

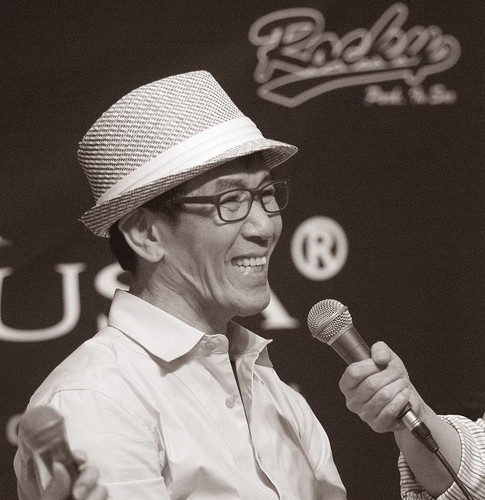

When news spread on Aug. 18, 2025 that Park Insu had died of pneumonia, many people stopped to remember him.

He was 78, and that number seemed to compress a long life into a moment for many fans and critics.

Seoul-based coverage supplied photographs and a steady account of the day, and listeners quickly revisited his signature song, "Spring Rain" (1982).

According to background reports, Park was born in 1947 in Kilju, in what is now North Korea, and was separated from his mother during the Korean War before being adopted and raised in the United States.

This American upbringing matters: when he returned to Korea and began performing in U.S. military clubs (the so-called M8th Garrison or US Army club circuit), that experience shaped how he sang and moved onstage.

During the 1960s and 1970s those venues were conduits for American Black styles—soul, rhythm and blues—and Park is often credited with bringing a soulful singing approach into Korean popular music through that route.

A beginning that felt like a stage made by listeners

The stage always seemed to come with him.

By the late 1960s, through contacts with figures like Shin Jung-hyun's circle, Park began to add a new vocal color to Korea’s pop landscape.

Meanwhile, his American childhood was not merely biographical detail; critics say it left traces in his phrasing, rhythm, and stage manner.

Experience on the US military-club circuit gave him repeated live practice, and that hands-on schooling may have been the most direct way soul technique entered mainstream Korean performance.

His 1982 single "Spring Rain" touched listeners with its lyrical tenderness and warm tone, and it helped register Park’s name with a wider public.

However, the road that followed was not smooth. In the 1990s a marijuana-related incident and other personal issues curtailed his career and created gaps in his public presence.

He made comeback attempts—he contributed to Shinchon Blues' debut in 1987, for example—but those moments did not erase the deeper scars that affected his later life.

A small ripple that made a large wave

Musical influence often spreads slowly but deeply.

Park’s role in introducing soul technique did more than transfer a set of vocal tricks: it broadened the emotional palette available to Korean singers.

The rhythms and vocal colors he brought from US-style clubs offered younger musicians new possibilities for expression, and in that sense he acted like a boundary-expanding experimenter.

At the same time, "Spring Rain" created a popular empathy that fit its historical moment.

The song’s melody and words resonated with the moods of 1980s Korea, and so its success was not only a personal achievement but also a small wave that helped push a genre forward.

Why we should remember his contribution

Memory can be both an obligation and a form of justice.

Park’s legacy resists simple praise or condemnation.

On one hand, he is widely regarded as a pioneer of soul singing in Korea. On the other hand, the marijuana incident and later personal troubles left a blemished public record.

These conflicting memories reopen questions about social stigma and the supports available for artists in trouble.

Old recordings, interviews, and performance footage preserve the era he lived through and the particular path he walked: a war orphan, adopted abroad, returning to Korea to act as a cultural bridge.

His life is both a personal story and a slice of social history. How we remember him raises broader questions about entertainment-industry welfare and historical judgment.

Park Insu as the godfather of Korean soul

It is hard to make absolute claims, but the evidence is difficult to ignore.

Music historians and critics often name Park among the representative figures of Korean soul. His vocal style and his presence on earlier stages likely filtered into the practices of later singers.

Therefore, his life and traces deserve preservation as part of music history.

On the other hand, it would be simplistic to treat his fall as only personal failure.

After the marijuana incident, social stigma, lack of medical support, and weak safety nets for aging entertainers compounded the tragedy of his later years.

Seen that way, Park’s case asks us not to reduce the story to individual fault but to examine structural failures in support and rehabilitation for artists.

Two opposing views: contribution

Arguments that emphasize his musical contribution are persuasive in several ways.

Park’s early performance path appears to have been a key channel for soul phrasing to enter Korean pop.

Spaces like US military clubs were more than entertainment spots; they were cultural exchange hubs where sounds formed and spread to domestic musicians.

Therefore, Park’s stage habits and vocal tone may have shaped a generation of creators.

Moreover, hits like "Spring Rain" show his artistic sensibility meeting public taste.

The 1982 release left a mark on listeners with its lyrical mood and melodic feeling, and that public recognition supports claims of artistic achievement.

From a music-history perspective, there is reason to credit him with helping introduce and popularize a genre.

Historical comparisons strengthen this view: worldwide, genre spread has often depended on individuals and particular venues. In Korea’s case, Park can be read as one of those influential figures who stood at a turning point for a new sound.

Two opposing views: criticism and social responsibility

But the critical view also carries weight.

The marijuana episode and other personal troubles affected his public career, and the resulting hiatus is undeniable.

Some insist his downfall should be seen through the lens of personal choice and responsibility, and they argue that an artist’s moral conduct matters for public life.

Meanwhile, others point to larger social failures surrounding his final years.

Reports that he ended up on basic social assistance and later suffered from Alzheimer’s while receiving inadequate medical and welfare support reveal problems that are hard to dismiss as purely personal.

The lack of robust pension, rehabilitation, and medical programs for entertainers has been raised repeatedly, and Park’s life starkly illustrates those vulnerabilities.

These two strands of argument are not just for-or-against judgments. Rather, they turn on how society allocates blame and responsibility.

Some emphasize individual accountability; others highlight systemic gaps—both positions will shape cultural policy and welfare debates going forward.

Conclusion: what remains and what we should do with it

Closure is never easy—but it is necessary.

Park Insu’s life remains a complex weave of musical contribution and personal failure.

His work likely helped the soul genre spread in Korean pop history, and his frail final years exposed weaknesses in social safety nets for artists.

In the end, we must decide how to preserve his musical legacy and how to reinterpret the causes of his decline in social terms.

Which memory matters most to you?

Will you first recall the talent and creative spirit, or will you give priority to the social responsibility to care for artists in need?

This question extends beyond Park Insu; it asks us to reflect on culture and welfare in our society.

Park Insu is widely regarded as a pioneer who introduced soul singing into Korean pop.

His signature song, "Spring Rain" (1982), helped form a popular resonance and likely aided the genre’s spread.

At the same time, a marijuana-related scandal, the interruption of his career, and his later descent onto basic welfare highlight weaknesses in support systems for entertainers.

Therefore, his life prompts simultaneous discussions about musical contribution and social responsibility: we should preserve his artistic legacy while reexamining safety nets for artists.