Its story begins when a skeletal remain from a disappearance forty years earlier is found.

Director Yeon Sang-ho builds a strong social argument on a modest budget.

The film examines both personal wounds and collective indifference at the same time.

Why does The Ugly force us to name what we avoided saying?

How the case opens the story.

Discovery upends everything.

The unearthing of Jeong Young‑hee's skeletal remains—missing for forty years—does more than restart a cold case.

The film uses that discovery to dismantle family memory and community silence.

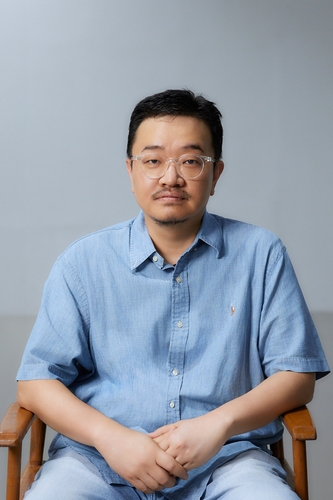

Yeon Sang‑ho, who adapted the story from his own graphic novel, wrote and directed the film.

He avoids sensational shock and instead focuses on relationships and social context.

As a result, viewers meet moral questions before they feel the thrill of mystery-solving.

The story asks about our gaze and our responsibility, not only about one person's death.

The search led by blind artisan Im Young‑gyu, his family, and documentary producer Kim Su‑jin expands into a social indictment.

At that point the film places private tragedy alongside structural indifference.

Background and the director's intent.

His aim is clear: ask ethical questions rather than chase commercial codes.

The film's English title appears as "The Ugly."

That label points beyond plain physical appearance to the social stigma and the ugliness that lives inside institutions and attitudes.

The director intentionally rejects his earlier sensational style to push a weighty narrative.

Working with limited resources sharpened cinematic choices.

Each shot and cut helps define the film's moral outline.

Therefore, audiences must read both emotional beats and the surrounding social context together.

Voices in favor.

The message is clear.

Many critics and viewers praise the film as a brave confrontation with stigma and hatred in Korean society.

In particular, the film's relentless look at how prejudice and indifference destroy a life has been widely commended.

"It asks the community to answer for itself rather than simply judging an individual."

Observers welcome Yeon's stylistic shift as artistic growth.

Aside from viewers who wanted his former shock-driven approach, the sober tone is read as deeper craft.

Performances by Park Jung‑min, Kwon Hae‑hyok, and Shin Hyun‑bin give the film emotional ballast.

Supporters also argue the film can spark public conversation.

They hope it will make issues like appearance‑obsession, social stigma, and structural discrimination part of a wider debate.

By revealing family trauma, artisan labor as a profession, and psychological burden, the film can have social use beyond entertainment.

Voices of concern.

The pace is slow.

Critics say the deliberate tempo and heavy themes make sustained audience engagement difficult.

Some members of Yeon's fanbase expected more sensational thrills and expressed disappointment.

The material and scenes may also cause psychological discomfort for some viewers.

Showing society's ugly face so plainly can provoke anger rather than empathy.

On the other hand, commentators raise ethical concerns about re‑exposing victims' families to pain without sufficient care.

From a commercial angle, doubts remain.

Low budget plus a solemn story could limit screenings and box office returns.

Critics worry the film may struggle to balance artistic intent with financial sustainability.

Deep comparison of opposing views.

The issue is not simple.

Both supporters and critics present grounded arguments, which makes the debate meaningful.

Supporters stress the role of a social message.

The film links family secrets, the specifics of a craft, disability, and caregiving into a single frame to ask about collective responsibility.

For example, the blind artisan's story shows where "occupation" and "care" overlap in ways the audience rarely examines.

"This work can turn an individual's wound into a public problem."

Critics, however, emphasize audience experience and psychological safety.

Artistic authenticity aside, excessive discomfort can block communication with the public.

That, in turn, may inhibit the spread of the film's intended message.

So the debate goes beyond right or wrong.

It requires a layered assessment of ethical clarity, rhetorical effectiveness, possibilities for empathy, and commercial viability.

Worries that deserve attention.

Sensitivity is a practical problem.

The social strife the film provokes may be an intended effect, but it can also re‑traumatize those directly involved.

Reopening an old case can place psychological burdens on victims' families.

Filmmakers and distributors should plan follow‑up measures that consider this sensitivity.

Publicizing the film's concerns is important, but exposure without care risks causing further harm.

Online reactions are polarizing.

Some praise the work for prompting reflection; others refuse to engage or report strong disgust.

That polarization suggests the film could become a flashpoint for social conflict.

Ultimately, cinematic approach is a choice.

Direct confrontation with social problems deserves respect, yet the method and tempo should be reconsidered.

Balancing genre expectations and ethical responsibility remains key.

In‑depth analysis: causes and reactions.

Causes are complex.

Appearance‑obsession and stigma, the film shows, were formed over time by family dynamics, schooling, and media messages.

The film makes structural issues visible through individual experience.

It carefully shows how Im Young‑gyu's ignorance, family secrets, and community acquiescence combined to produce tragedy.

This is not just a crime story; it is a call for ethical reflection.

"The eyes that turned away eventually made the case."

Online comment threads became an outlet for emotion.

Praise centers on courage and stylistic change; critique highlights discomfort and worries about box office prospects.

Those reactions indicate how strongly the film stirs social imagination.

In the end, the film's value depends on its ability to open dialogue with viewers.

When the message expands common ground for empathy, social impact grows.

Conversely, when it produces disproportionate discomfort, public debate may dim.

Summary and policy implications.

The film is more than art.

The questions The Ugly raises should move into cultural discussion and policy debate.

Strengthening prevention, education, and victim support systems is necessary.

In particular, schools and families need preventive programs about appearance‑based stigma, and mental‑health and caregiving services should be expanded.

Also, media must follow ethical guidelines in reporting and narrative construction.

Conclusion: time for reflection.

The central point is clear.

The film compels us to examine our gaze and our duties as a society.

Despite budgetary limits, the director opens a conversation that audiences must answer.

The Ugly asks for reflection through discomfort.

Yet for reflection to turn into healing, practice and care—empathy and tangible support—must follow.

Which part of this film's questions resonates with you most?