The film turns a private confession into a public conversation about family harm.

The director traces a path toward reconciliation with his mother and offers a quiet message of healing.

At once empathetic and unsettling, the film asks viewers to sit with discomfort as part of understanding.

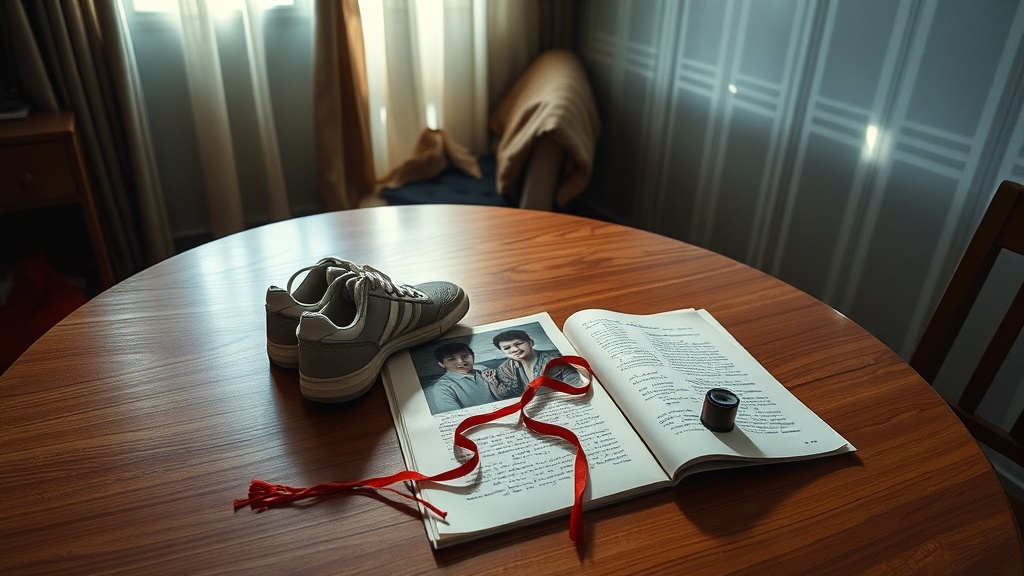

Suchi's confession: wounds and reconciliation on screen

Overview

The story begins as a personal account.

Director Suchi places his childhood experience of domestic violence (abuse within a family) at the film's center.

He reconstructs memories on camera and, meanwhile, invites the audience to ask difficult questions.

In this way, the film probes where structural causes of family violence intersect with personal feeling.

This film attempts to move a private wound into public view.

At times that effort brings comfort to viewers, and at other times it creates unease.

However, the film's aim is not simply to catalog emotion; it seeks to reinterpret relationships and their legacies.

Background and context

The film lives between record and reenactment.

Unlike his earlier films, Suchi ties his labor and identity directly to his personal history.

In other words, a private domestic space becomes a subject of public scrutiny—and that tension is central to the work.

In South Korea, as in many countries, family problems have long been hidden by customs and institutional blind spots.

Meanwhile, contemporary culture—especially film and television—has begun to surface those issues more openly.

Suchi's film fits into that trend, using a personal confession to broaden public empathy and awareness.

The confession and artistic choices

A confession doubles as a directorial method.

Suchi carefully shapes the film's visual language as he reconstructs his memories.

Camera placement and editing, meanwhile, steer viewers toward encountering uncomfortable truths rather than toward easy emotional manipulation.

Consequently, the film asks not only for sympathy but for narrative accountability.

Balancing cinematic truth and personal testimony is the film's core challenge.

That balance shows itself in the crack between self-censorship and disclosure.

Meanwhile, viewers bring their own histories into that crack and read the film in varied ways.

In support: the value and social ripple of confession

The confession can be necessary.

Supporters see the film as a candid, victim-centered confession.

Suchi turning his pain into art is read as both artistic courage and social contribution.

Crucially, naming violence that happens behind closed doors gives voice to hidden harms.

From this angle, the film does more than record a life; it can kick-start public debate.

First, turning a survivor's experience into a story can broaden understanding beyond mere pity.

Second, by moving private matters into the public square, the film can point toward the need for institutional reform.

Third, art sometimes shifts public perception faster than policy does.

In practice, media attention often leads to increased use of counseling services, improved protection systems, and renewed legal discussion.

For example, after several films and series tackled family abuse in recent years, local hotlines reported higher call volumes and community groups argued for policy changes.

Suchi's film could produce similar ripple effects.

Public confession can spur better victim support and institutional reform.

At the same time, forming social consensus increases the need for prevention and education.

Ultimately, artistic confession can act as a mirror to test social safety nets.

Against: privacy and re-traumatization concerns

The cost is real.

Critics worry that the director's disclosure may inflict further harm on family members and on the director himself.

When private conflicts are made public, the people involved can face added psychological strain and social stigma.

Protection of the reputation and privacy of family members accused or implicated is therefore a sensitive concern.

Moreover, if a film relies too heavily on a single personal narrative, it risks missing broader truths.

Narratives that emphasize emotional appeal may win sympathy but offer weak structural analysis or preventive solutions.

As a result, some viewers may criticize the film as eliciting pity without driving real change.

Additionally, public reaction—especially on social media—can intensify harm.

Personal intention can be distorted, and discussions may reduce complex situations to simplified labels of 'perpetrator' and 'victim.'

In that context, opponents ask anew how to balance artistic freedom with protection of private life.

Privacy safeguards and mental health supports must come first.

Expecting a film to serve as therapy is risky.

Filmmakers and producers should provide psychological support during production and clear guidance and warnings for audiences.

Deeper contrast: cases and comparisons

Comparisons clarify approach.

Works around the world that deal with family violence take many forms.

Some foreground survivors to demand solidarity and policy change, while others explore the perpetrator's context to seek causal understanding.

Suchi's film tries to do both: it confesses and it aims at relational repair.

For example, a film shown at an international festival partnered with victim-support groups to host post-screening discussions.

That collaboration led to local counseling initiatives and policy proposals.

In contrast, films that only depict suffering without organized follow-up often leave viewers feeling moved but powerless.

Suchi's film sits between these two tendencies.

Therefore critics and audiences should judge it by both immediate impressions and long-term impact.

When policy conversations and civic responses accompany art, the chance of social change grows.

Precautions and recommendations

Management and care are essential.

To avoid re-traumatizing the director during production, professional mental-health support should be in place.

Planning for counseling and safety nets needs to start in preproduction.

Moreover, public discussion of family violence must prioritize victim-protection principles.

Because the film may draw public attention, it should be linked to efforts that expand services and protections.

Prevention education in schools and communities, stronger counseling networks, and legal safeguards can turn initial reaction into lasting change.

Art can name the problem; institutions must translate that recognition into concrete reform.

Conclusion and questions

The point is clear.

Suchi's film turns personal pain into art, and that act generates both empathy and debate.

The film exposes a sensitive family space and, in doing so, calls for careful protection of those involved and for a balanced narrative that does not oversimplify.

A film can start a public conversation, but solutions come from solidarity and institutions.

In short, the work shows that artistic confession has the potential to prompt social change.

Do you think this film's public airing can lead to real policy shifts and better support for survivors?